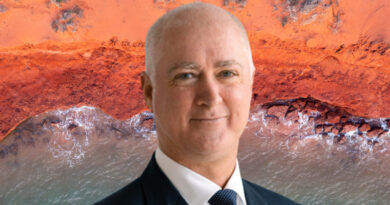

George Long: “Any time a market crashes, there will always be opportunities”

The LIM Advisors Founder and CIO George Long talks to Hedge Funds Club’s Stefan Nilsson about the Evergrande crisis and the opportunities and threats that come with it in China and the world.

George Long is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of LIM Advisors. George established LIM in 1995 and has more than 40 years of Asian investment experience. In 1990, George established and ran the Asian Investment Management division of what became Barclays Global Investors. Prior to joining Barclays, George was CIO of Gartmore Asia investing across Asia. Before that, he was Head of Korea for Indosuez W.I. Carr Securities. He started his career at Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company (now part of JP Morgan) as an international banking officer. George has been on the board of governors of the CFA Institute. He established the Hong Kong Society of Financial Analysts in 1992 and was its President for eight years. He also set up the Hong Kong & China Chapter of the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA) in 2002 and was its Chairman for five years.

Let’s talk about China and the threats and opportunities that come with the Evergrande crisis. I understand that you have been buying distressed bonds of Chinese developers. What can you tell us about how you view the current situation?

We have started buying a little exposure to Chinese offshore high-yield and distressed bonds, both in the real estate sector and in other sectors given the massive sell-off in such bonds over the past two or three months. We have not been buying Evergrande bonds however as this is too complex of a situation. Any time a market crashes, there will always be opportunities. And many Chinese property high-yield bonds have crashed. I think this could be a tremendous investment opportunity but I also think it is a very complicated and fluid situation. It will probably take a few more months for the bond market to actually settle down at the right price for these distressed names. It will probably then take a few years for the underlying fundamentals to be worked out for each distressed name depending on the individual company, overall government policy and the condition of the property market in China.

The US$55 trillion real estate market in China is quite possibly the most important sector in the global economy at the moment. What impact do you think the ongoing situation will have outside China?

First, there is some disagreement about how large or important the property sector is to China, even though clearly it is important. Obviously, a massive property market collapse in China, if that happens, will have negative consequences for domestic demand in China, and this would probably feed through to lower global demand since China is now the largest trading country. On the other hand, this will probably mean that China’s monetary policy will be easy, which would be in contrast with upward interest rate pressure in the US and elsewhere. The Chinese government has a great deal of interest in not allowing the property market to suffer a massive sustained crash even though they want to damp down property speculation and excessive bank lending and rein in some out-of-control individual property developers. Therefore, I do believe there will be various initiatives to help support the property market in general. In fact, we are already seeing some policies focused on making mortgages easier to obtain as well as the recent lowering of the reserve rate requirements for banks, adding credit to the market and alleviating some of the pressure. The Chinese government will want those buyers of apartments under development who have already paid deposits to eventually receive their apartment, so I believe the government and banks will work at the individual project level to make sure most property projects are completed. This will also be good for the many suppliers and contractors. However, I don’t think this approach will benefit offshore bondholders per se, even though it is not designed to hurt them as some market participants seem to now believe. The holders of many offshore Chinese distressed property bonds could receive very low recoveries. This could shut the capital markets for most Chinese high-yield and property names for some time. These losses, combined with losses this year from Chinese ADRs in New York, will sour some international investors on China for a long time.

How do you manage your funds’ risk when it comes to Chinese securities? In the case of Evergrande, it seems awfully complex with many unknowns.

We are not actually involved in Evergrande’s bonds and probably won’t become involved. We did actually hold some Evergrande bonds in 2020 but sold them over a year ago, as we came to the conclusion that the risk-reward was not in our favour given the size and complexity of the situation. I think the situation is still too complicated and opaque for us to figure out. When you talk about managing our funds’ risk of investing in China, there are different risks to consider. In terms of Chinese offshore bonds, there are specific risks such as individual company credit risk and structural risks of the bond instrument. Detailed fundamental credit analysis, which we have been doing for more than 25 years, can often mitigate these risks. I trained as a credit analyst in New York covering Asian credit in my first job. In terms of the domestic Chinese A-share market, there is a lot of volatility risk but good volatility risk management can mitigate this. The offshore ADRs have always had particular risks such as the Variable Interest Entity or VIE structural risk and well as US regulatory risk about accounting standards. Other risks, such as RMB currency risk, work in our favour. A lot of international investors in 2021 are talking about regulatory risk in China. Regulatory risk is more complex, especially since the government and party in China have been talking about controlling both monopolistic tech models and for-profit education for some time but I think these signals were largely missed by the international investment community.

Shorting in China is expensive and difficult. How do you tackle this?

For shorting A-shares, which right now can only be done offshore via a swap, availability is a much greater issue than it being expensive, although it is expensive as well. In the past, we have sometimes hedged overall A-share market exposure via swaps or futures on an A-share market index when we had broad underlying long exposure we wanted to hedge. That can act as a general equity market hedge but has a lot of basis risk if one is trying to hedge individual names. We rarely short high-yield bonds because the negative carry is so high and often the borrow is unstable.

You have many years of experience investing across Asia, including holding Japan, Taiwan and Korea-focused roles earlier in your career. Apart from Chinese debt, what kind of opportunities are you currently eyeing in Asia?

The domestic Chinese convertible bond market is really interesting and a great opportunity. I have been involved in Asian convertible bonds for something like 34 years and the A-share convertible market, which is growing quickly and is highly inefficient, is one of the best convertible opportunities I have seen. There are a number of reasons China onshore CBs are attractive. The unique conversion price resets and bond floor prices effectively mean there are ways to generate an asymmetry of returns with downside protection like fixed income but upside participation like equity. In April 2021 we launched a long-only fund to invest only in Chinese A-share CBs, and the fund is up more than 22% since inception to the end of November 2021, outperforming the majority of alternative routes to China exposure, both onshore and offshore. Our team’s approach to buying cheap bonds with strong upside has captured gains in a number of stocks and industries including EVs and solar panel component manufacturers. I am also bullish on Japan activism and equity event opportunities in Japan. The corporate scene in Japan has really changed and there are many inexpensive stocks where value is starting to be unlocked, partly through the efforts of outside activists. We have been doing shareholder engagement and activism in Japan, first in the bond market around 2009 and then in the stock market since around 2015. We launched a Japan multi-strategy fund in 2002 and restructured it to an event and activist fund in 2019 to help unlock some of that value through engagement with the Japanese companies. We have a successful effort doing that.

LIM has been going strong since 1995. How does the company stay relevant?

If we can find good investment opportunities and produce good returns, we will be relevant. Every firm, and everyone, has to reinvent itself periodically while still staying focused on one’s core skill sets and disciplines. Our focus has changed through time as the opportunity set across Asia’s capital markets has changed. There is also structural and cyclical change in Asia and globally that we have to be aware of and benefit from. All this allows us to remain relevant and continue to find opportunities to generate returns for our investors.

What’s the biggest difference at LIM in 1995 and now at the end of 2021?

We are more experienced. We’re still hungry. We are again now a lean organisation, although not quite as lean as when I started the business. We have gone through a restructuring process over the past three years to make the business leaner and more focused.

How has the ongoing global pandemic impacted LIM’s ability to raise capital? Are you making use of virtual ways of connecting with investors when you can’t do too much travel and very few face-to-face meetings?

The pandemic has made it more difficult to raise money from international investors. We, therefore, have to make use of virtual ways of connecting. We are fortunate that we have such a strong and established brand in the hedge-fund world, allowing us to skirt some of the difficulties that the lack of travel presents.

You are 68 years old now. Any plans to retire? Or is it too much fun running money and you plan to carry on running LIM for many more years?

I am not yet 68 years old. I have no plans to retire. I like what I do. I love the markets and investing. I did try to build a succession team under me starting about seven or eight years ago partly in response to pressure from some of our investors and investment consultants. Frankly, that didn’t work very well, and all that happened was that I spent too much time on people management and our returns went down. A friend of mine who is about my age works for one of the greatest Asian businessmen who happens to be over 90. The businessman asked my friend if he was about to retire and told my friend: “Don’t retire on me. You are just reaching your prime. You have at least another 20 years left. I need people like you who have real experience.”